Lawyers and Developers, not so different May 11, 2014

Really

I have been developing software professionally since 1978. I went to law school (BU Law '91). I think that computer programming technology and the law are really, really similar.

At the end of the day, both law and computing is about wrapping abstractions around very complex interactions such that the rules are comprehensible and the outcomes are predictable.

At the end of the day, both law and computing are about giving individuals the ability to reason about the behavior of systems (people, groups, computers) based on a wide variety of inputs that cannot all be conceived of when the systems/laws are initially developed. Both the law and computer systems have ways of dealing with new, unexpected inputs: judges/common law and system updates.

Both US/UK law and computing have externally mandated requirements (legislature and language designer) and evolved requirements (common law and libraries/frameworks.)

Both law and computing have words for things that a person skilled in an area should deeply understand, yet the terms used are rather simple. In law, it's called "terms of art" and in computing it's called "design patterns."

Both law and computing have practitioners that spend many, many years understanding the state of the art and often influencing the state of the art and having the requirement that they are up to date in the state of the art in their area. Most practitioners of law and computing ultimately have very little influence on the overall direction of their field. Names like Hand and Brandies and Wadler and Hopper and known and revered in each of our worlds because they are the few who really made material differences.

Both law and computing necessarily have to evolve in ways that practitioners can keep up. Even "trivial" changes like the 1986 Tax Reform or Microsoft's .Net have taken years for practitioners in law and computing to fully understand and reconcile.

So, when a lawyer or judge says, "well, just go make a new language," ask that person when the next UCC will be happening.

When a lawyer or judge says, "there are lots of options for building software for a new phone," ask them what popular phone is built on a system that has less than 10 years of popular programming support. Hint, none. Apple's was built on OS X which was built on NextStep with was built on BSD Unix. The iPhone APIs are substantially similar to the NextStep APIs which were released in the 1980s. Apple had a 10,000+ strong developer network to draw from for iOS development. Windows Phone were built on Windows APIs that date back to the 1990s. Even Blackberry and Nokia used C, UNIX-style APIs, and popular windowing toolkits.

Just as a new approach to the law (e.g., the UCC which "merely" unified the standard business practices across states) requires many years, millions of dollars of effort, and a ton of training and learning and knowledge sharing, so, too, does a new approach to computing.

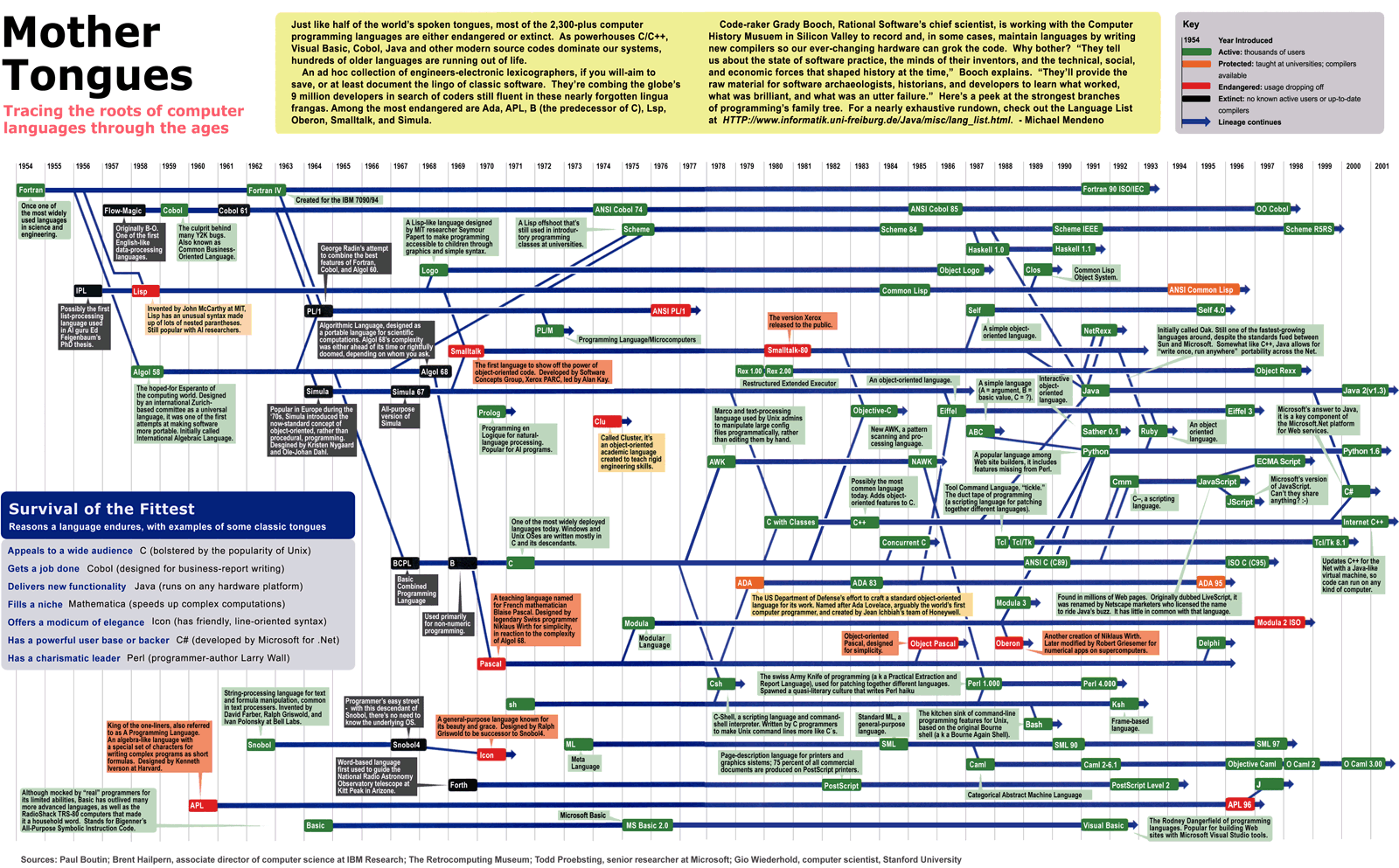

That is why there are very few "new" languages:

That is why most of the available languages derive from each other.

Just like Judge Blackstone is very alive in common law, Backus and McCarthy are very much alive in every line of code we write.

Just as the law is a 500 year chain of precedents leading to where we are today... punctuated by legislation... computer languages, systems, and APIs are a 60-80 year chain of design decisions and evolutions that lead us to where we are now. No computing system is done in a vacuum, just as no legal case is done in a vacuum. Learned Hand is perched on the shoulder of every sitting judge in the US. Just as Backus is perched on the shoulder of every Java and C and Ruby and Python programmer.

Just as every legal case is a necessarily and decidedly a derivative work of the prior art in the law, almost every computer language and library and API is a derivative work of what came before in computing.

We are not so different. Let's try to communicate to the law folks that computing art and systems have evolved much like the art of the law. It's not so simple to make sweeping changes. In fact, it's very, very costly.